Quad ESL Loudspeakers

Expectations have changed over the decades. In the 21st century, we demand amplifiers that deliver copious amounts of power with ease. Loudspeakers? We insist on dynamic range unimagined in the 1950s—beyond even what the horns of the day could deliver. Levels? 100 dB+ capability is the minimum. Bass? We expect our sound systems to loosen brickwork. And yet a speaker that could do none of those things, let alone handle an amplifier willing to feed it 30 or more watts, remains a permanent fixture in every knowledgeable audiophile’s Top 5 of the Greatest Components in History.

Expectations have changed over the decades. In the 21st century, we demand amplifiers that deliver copious amounts of power with ease. Loudspeakers? We insist on dynamic range unimagined in the 1950s—beyond even what the horns of the day could deliver. Levels? 100 dB+ capability is the minimum. Bass? We expect our sound systems to loosen brickwork. And yet a speaker that could do none of those things, let alone handle an amplifier willing to feed it 30 or more watts, remains a permanent fixture in every knowledgeable audiophile’s Top 5 of the Greatest Components in History.

At least, it does for those who have heard the British marvel, even if they weren’t around when the original Quad ESL went out of production in the early 1980s, to be replaced by the equally miraculous ESL63. But the Quad ESL—aka the ’57 by its fans, if not by Quad itself—remains the milestone, despite the ’63 reaching down lower and going louder.

One has to be in his or her early 70s to be able to recount the impact the Quad ESL had when it first appeared nearly a half-century ago. The finest speakers of the day—the still-with-us Klipschorn, the nascent AR range, the best of Tannoy—were and are fine performers, but the Quad did something that had nothing whatsoever to do with power handling, bass extension or maximum SPLs: It sounded real.

It remains, for many, the most natural-sounding speaker ever produced, a full-range electrostatic designed in the mono era, but which made the transition to the stereo era with such ease that there are those who today find it hard to better. My dear friend David Chesky, who knows a thing or three about recording, cherishes a pair he had rebuilt by one of the many specialist firms who keep the Quads alive long after the company itself stopped servicing them. They remain his standard, positioned next to a baby grand in his living room. I believe Art Dudley of Stereophile is a devotee. And the first time I met Gayle Sanders, the co-founder of MartinLogan, some 25 years ago, he told me that the Quad was his yardstick.

I certainly will never part with mine.

Styled to look like a room heater, the metal-grilled Quad, from about 80 Hz or 90 Hz on up, delivers neutrality that remains uncanny to ears that have learned to tolerate coloration, however minuscule or even euphonic. Many thousands of the 54,000 sold still survive, so one doesn’t have to search far to hear them. Any collective of like-minded music fanatics will number at least one who has a pair. The experience is unforgettable.

Their influence, despite being a full-range electrostatic and therefore not something easy to imitate, is widespread. In addition to inspiring Sanders, they surely must have been in the back of the designers’ minds when the Dahlquist DQ-10 was taking shape—and that’s a dynamic speaker, not a panel. Mark Levinson used stacked pairs as the basis for his HQD, which employed a pair of Quads per channel, mounted vertically, with the sound augmented by a cone woofer and ribbon tweeter, a speaker one maven tells me has yet to be bettered. And if that’s not enough, Quad 57s in quantity provided the sound in SME’s Music Room, until their successor, the ESL 63, arrived.

Why? Because they can sound so open and transparent as to redefine neutrality in an audio context. They reveal all a system has to offer. The price you pay is in the lack of level and extension. But, as the designer Peter Walker always maintained, like Rolls-Royce and its horsepower figures, the performance was always “adequate.”

Why? Because they can sound so open and transparent as to redefine neutrality in an audio context. They reveal all a system has to offer. The price you pay is in the lack of level and extension. But, as the designer Peter Walker always maintained, like Rolls-Royce and its horsepower figures, the performance was always “adequate.”

As the first commercially and sonically successful full-range electrostatic loudspeaker, the Quad was so radical and so far ahead of its time that one must marvel at the perspicacity of many of the 1950s audio critics who recognised this from the outset—which is not to say that it was an immediate hit, certainly not at £52 each (or roughly £2,200/$3,450 in today’s money). But many embraced it, even though it was, in the context of the period, a freak.

Because the Quad ESL was unique, Walker recalled that, “It just competed against other loudspeakers, and it wasn’t as loud, so people who wanted to shake the windows didn’t buy a Quad electrostatic speaker.” This affected sales, especially in the USA, where rooms were larger. But, as Walker also noted, “It wasn’t very good with American high-powered amplifiers, which would just bust ‘em, spark ‘em to bits.”

When stereo arrived, it gave the Quad a boost, because it meant that the task of filling a room was shared by two speakers. For stereo, it proved a revelation, suffering less of a hot seat than most dynamic speakers. The performance was (and remains) so convincing, despite its bass and level constraints, that the original ESL stayed in production until 1985, overlapping with the Quad 63 introduced in 1981.

Difficult to manufacture, easy to destroy with too much power, the Quad ESLs need the same gentle handling one would apply to driving a pre-WWII automobile. Used properly, with a mind-set appropriate to the era, the Quads will delight. I suppose one could buy multiple pairs, say six or eight panels per channel, if one was desperate to hear them delivering high levels, but a subwoofer à la the HJQD would still be required.

For people like Chesky, Dudley and a legion of devotees, a simple pair will do the trick. You just keep the levels down, and feed them something with which they synergize to perfection—better than the Quad IIs of the day are the Radford STA15s or STA25s. Set them a third of the way into the room. Close the door, sit in the apex of the triangle and play whatever you like, though Walker will be looking down from heaven with a scowl if it’s anything other than unamplified classical music or maybe jazz.

In my experience, nothing matches them for vocals. The closest I’ve heard to their sense of realism are Apogee’s Scintilla, the BBC LS3/5A and the Stax electrostatic speakers, especially the F81. The Quads deliver pinpoint imaging, and they truly “disappear” within the soundstage they recreate. The spread is so seamless that one is hard-pressed, with eyes closed, to locate them in the room. Treble is sweet, transients fleeting, textures palpable.

Even if you have no desire to own a pair, do try to hear them. If one were to create a list like those ‘50 Things To Do Before You Die,’ then the Quad ESL 57 would figure on ‘50 Hi-Fi Components You Must Hear Before You Die’.

When asked in the 1990s how he would he have improved the speaker, Walker admitted that he was limited by the technology of the day, and that he did the best he could at the time. “Would I have made it bigger? Well, then it would have upset a whole lot of people who wanted a small speaker. Would I have made it smaller? No, because then you wouldn’t have enough bass. It was roughly the right size.”

Which is a typically understated, entirely English way of describing a frickin’ masterpiece. -Ken Kessler

ORIGINAL QUAD ESL SPECIFICATION:

ORIGINAL QUAD ESL SPECIFICATION:

Frequency Response: 45 Hz – 18k Hz

Impedance: 15 ohms

Mains Consumption: 6W

Dimensions: 33x25x3in (WHD)

Weight: 35lb

Original Price: £52

Numbers produced: 54,000

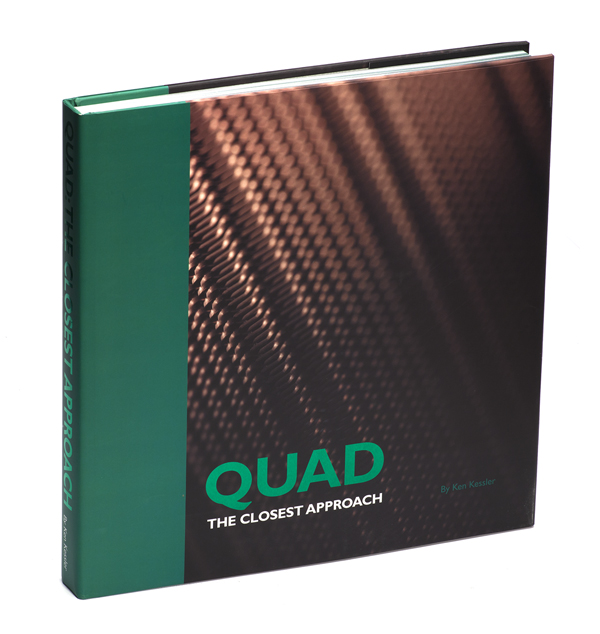

Ken Kessler is the author of QUAD: The Closest Approach, the official history of the company.