posted: August 26, 2025

Looking back on DEVO…

This article, originally titled, “Almost everything you want to know about Mark Mothersbaugh,” is written by Jaan Uhelszki, and was originally published in issue #26 of TONE, back in 2009. Considering the popularity of the recent DEVO documentary on Netflix, we felt it might be fun to look this one over again.

Mark Mothersbaugh would be loathe to be called a Renaissance man, but that’s what he is. Rather a savant for most of his years, he got the name and idea for his revolutionary science-cum-art rock band from a Jehovah’s Witnesses pamphlet, and nabbed the phrase, “Are we not men? We are Devo,” from a 1932 Charles Laughton movie called Island of Lost Souls. An odd title for a man who has a preponderance of soul, even if he is from Akron, Ohio.

In addition to being the bespectacled, robotic lead singer of Devo, the 59 year-old Mothersbaugh is a well respected film composer, with over 100 credits. He wrote the music for Pee-wee’s Playhouse in 1986 –and even got to sit on Chairy. He’s an accomplished artist in the “low brow school of art,” mainly because he incorporates flourescent pigments in the base of his paints so they glow when you least expect it — much like the occasional subliminal messages he inserts into the commercials he creates, signifying only one thing: With Mark Mothersbaugh, what you see is not what you get. But what you get is a lot.

With Devo back on tour and a new album in the works, our favorite spud boy is as busy as ever.

TONE: What’s the greatest misconception about you?

MM: Oh, good grief. The greatest misconception is that “Whip It” was the best thing I ever did.

That’s the song with the gift that keeps on giving, you know?

Yeah, all the way to being the theme song for the Swiffer Wet Jet commercial!

You did that commercial? Now, that’s de-evolution. I have to tell you it’s probably the worst product ever made for man.

It is. I got this little tiny old, inexpensive house out in Palm Springs, fixed it up really nice so it had a nice epoxy floor. And oh, there’s a little spot over there. I got the Swifter out. I’ll try it. It ate the epoxy right off the floor. Whatever it is, I don’t know, but I think it came from outer space. I don’t know if we’re even allowed to dispose of it in your trash.

You should retaliate and put subliminal messages in those commercials.

I love to put subliminal messages into commercials. It’s easy to do. We used to be into it more than we are now because nobody cared. I kept putting these messages in and nobody ever stopped or called me or got freaked out and said, “Take that out immediately!” People just acted like they didn’t hear it.

How did you feel when Target used “Beautiful World” to sell soap?

Well, we really liked the idea. The only thing is the ironic humor was lost on them. People that really know the song, and know “It’s a beautiful world for you / But not for me,” would appreciate it even if those words weren’t used in the actual commercial.

Tell me about the importance of being from Ohio.

Ohio had everything to do with my band and myself, the people in my band and myself, our vision of the world and the particular viewpoint that we have, and have had since we were angry young men. And now we’re grumpy old whatevers.

My mom always tells me that men get meaner as they age.

I don’t think men get meaner. I think what happens, as they get older and then as lust fades away, they become more like women.

Are you the oldest kid or the youngest?

I’m the oldest kid.

Did you fit in in school?

I was kind of a loner and I fought with the teachers and I fought with the other kids. I got my ass kicked by everybody when I was in school, so when I left, when I went to Kent State. I liked it because I was anonymous. At 3:30 the bell would ring and all the kids in my class, they’d all perk up … And then they’d head off for their fraternities and their sororities and their beer houses and all the things they did, and I just stayed right there and I used all the facilities in the art department and just kept doing art all night. Did it till one or two in the morning and then get up and go to my classes and just wait for everybody to leave again.

I remember in an interview in the ‘80s you said that you’re a picky eater, so was a big deal when David Bowie asked you out for sushi? Did you eat the raw fish?

I did. When David Bowie asks you to eat raw fish, you say “Yes.”

So David Bowie cured you of being a picky eater.

Yeah I pretty much got over my picky eating because of David Bowie. That, and seeing the world. But my eating habits were partly economic. I used to think food was like something to take your money away so you couldn’t afford to buy a roll of recording tape that week and record a song.

During Devo’s heyday, when everyone from Mick Jagger to Jack Nicholson to Eno were asking to be your guest list and saying that you were such a revolutionary band, did you think you deserved all that high profile attention? And were you nervous when people would come backstage?

I don’t know, I was kind of nerdy. I was the guy that was happiest sitting at, before there were computers, sitting at whatever instruments I had and making music or making visual art – that’s what made me happy. In a way, I wish I would have been more interested in meeting people and hanging out with the people that wanted to collaborate with us and stuff. And I did some collaborations. We worked with Eno and Bowie, of course. And I played on a Rolling Stones song, and I wrote some music for Hugh Cornwell and the Stranglers, and did some sessions but not all the stuff that we could have done or that we were offered to do, so it’s like in retrospect I kind of wish we would have been a little less insular as a band.

Yeah, but maybe that would have changed like your vision, too.

That’s what we thought: We don’t want to be a rock and roll band. We didn’t think of ourselves that way.

Yeah, Devo was more like an art statement.

That’s how we felt about it.

I always think that we’re all the same. It doesn’t really matter if Mick Jagger wants to collaborate with you unless you have had a meeting of the minds, you know? But I could see where there was some kind of intersection between Devo and Eno.

Yeah. That was during the Roxy Music days.

Eno always seemed like a space alien to me. Did he ever come off his pedestal? I mean, did you guys communicate well?

It was funny, Eno was one of the few people I had kind of like some sort of a reverential feeling for and I kind of lost it. I still think he’s a great guy, but … it’s really hard to pinpoint incidents, but you know, after we finished, I never thought of him in the same way. But having said that, I always thank him because he paid for the first Devo record for us, because we didn’t even have a record deal.

I read that Iggy was also instrumental in getting you signed?

Iggy, David, and Brian Eno all took an interest and actually were all proactive in helping us.

Now you spend most of your time scoring films and creating music for commercials. Did you feel like getting into the film music business was serendipity? Is it something you went after or did it just kind of fall into your lap?

Well, I always liked film music, but I didn’t go to school to be a composer. I went to school and didn’t know what the hell I was doing there, and then became obsessed with printmaking and then met Jerry [Casale], who I started the band with. Then everything just started falling forward.

I know you named your band for de-evolution, but don’t you feel like everything’s been like an evolutionary progression, like it’s built on each other? Or has it just been like a lot of random accidents?

I think there’s an intelligent design at work here. What’s all this bullshit about evolution and intelligent design? It’s de-evolution! Nobody knows, they’re just like ignoring the facts. Pay attention to what’s going on!

Was there a watershed moment when you really thought you got to a nadir of de-evolution, that you were prescient in your ethos?

To me it was MTV. MTV was exactly what we were predicting. Sound and vision. We were reading Popular Science. We knew about laser discs, and said, Oh, my God, it’s exactly the same size as an album but it has pictures to go with the whole thing. This is going to totally change who’s making pop art. It’s not going to be some guy sitting over there with a band in a bar, and it’s not going to be somebody that’s sitting on a hill painting a landscape, it’s going to be somebody that works in the pop media of our time. They’re going to be doing stuff that goes on television and it’s going to be music and pictures together. And that’s what we wanted to be. We wanted to be the new art form. And instead MTV came along, and it looked like, during first half a year or year, it had potential. And then all of a sudden, I remember having this realization that MTV was just Home Shopping Network for record companies.

It became less a thing of making albums; you were just making one song. And one song that was going to get on MTV because if it didn’t, you were fucked. And your whole project died, and all the money that you would have used to like seed yourself to keep going till you had your third album and maybe had a chance to have enough maturity to make a statement that was interesting from an art point of view, people never got there.

Make it one step more depressing. Oh, I know. Let’s change the format to CD’s, where now all of a sudden people feel like instead of writing 44 minutes of well-crafted music, they have to come up with 70 or 80 minutes of filler to go around the one song that’s on MTV. So you got one song for MTV and then you got 70 minutes of stuff just to fill up a CD.

Was that really anxiety-producing for you when you were in the band?

Well, by the time, our airliner was already heading to the ground where CD’s were concerned and we were weaving a cocoon to hibernate in at that point. So we saw it more than we felt it. It was already a virulent strain of anti-art that was like a gas permeating the industry, and for some reason it made record companies hopeful. It gave them a new lease on life because they reissued all their old shit. And then they went into horror when they realized, “Oh, but wait. Once we give it to them in digital form, then that’s it. They will share it with each other and they don’t need us anymore.”

When you were in the throes of Devo, did you know how cool it was? Did you have that sense that you were doing something really tremendous?

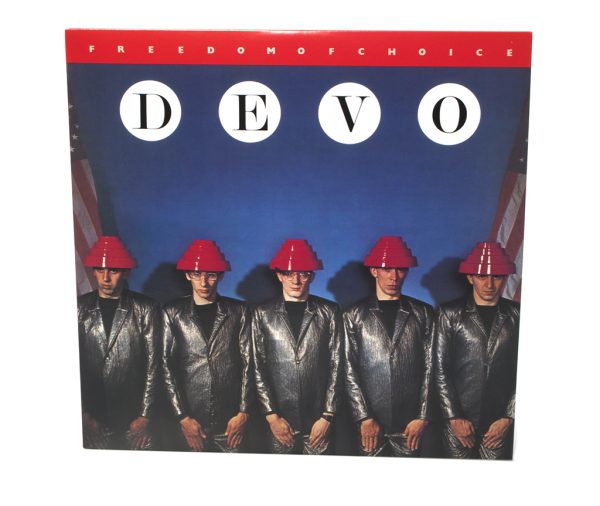

We felt like we were doing something big in the early days. There was that energy that started it. And then by the mid-to-late ‘70s, we had that power and that energy of things moving forward. And then we went into retrograde, then with the Freedom of Choice album it started heading downhill, there was this horrible feeling where we felt misunderstood. We felt like—”wait a minute, we have something to say, and there’s a lot of people that don’t have anything to say, and you should ignore them!” It was a frustrating thing. I never anticipated it, you know. I didn’t know then that things were cyclical and they came back. Like careers.

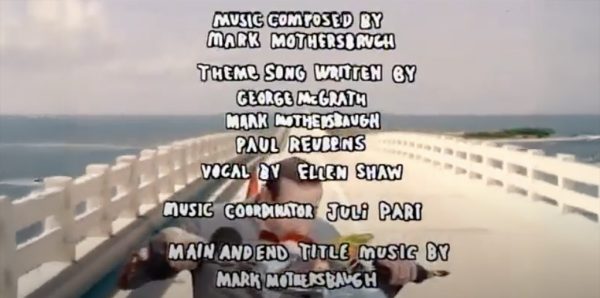

Your career came back when you did the music for Pee-wee’s Playhouse. Were you asked to do it because Paul Reubens was a big Devo fan?

Yeah, I’d known him for years, and he’d asked me to work on his live theater show. He asked me to score his film. And I was too wrapped up in Devo and I was traveling all over the world. I was interested, but you know how it goes. When the TV show thing came up, my drummer had just left the band to start another band. Greta, Greta. You don’t remember that? Nobody does.

When you worked on Pee-wee’s Playhouse did you hang out there a lot?

When you’re a composer, especially for TV but for film also, you spend a lot of time by yourself. It is much more solitary than you would imagine. I visited the set once when they were shooting in New York for the first season, and I sat on Chairy. The rest of them were all easier because they shot them in L.A. I’d go visit, but most of the time, I got a tape on a Monday and sent it back to them on Thursday, and watched it on the weekend.

Is the process different than writing a rock song? Do you have to use a visual kind of sense?

I don’t know how to compare that kind of writing to a rock song because when we did songs, we were thinking about sound and vision. And we oftentimes had ideas for films before we wrote the song. Write a song to go to a film idea that we were talking about, because we made our own little films, back when they were still called promo videos.

How did you get the gig doing the Rugrats music? Were the Clasky Csupo people pretty wacky or were they fairly normal?

Gabor Csupo, of Klasky Csupo called me and wanted to license a song from Muzik for Insomniaks, a solo album I recorded in the early ‘80s. I offered to write him something new, and a great collaboration was born. All people in animation seem to be pretty wacky, yet somewhat normal.

And the Sims video games?

That was actually Mutato Muzika, my West Hollywood muzikal think tank (www.mutatomuzika.com) that scored many of those Sims games, but Devo would be a perfect fit… Wait, didn’t they license an unheard Devo tune called, “i’ve fallen in love, (with recombinant dna)” for a WB trailer, or something?

Mutato Muzika has scored many big games, and Devo has contributed to a number of games, also.

What was the greatest thrill being in Devo?

To actually be able to pull it off. I think it’d be great if everybody could at one time go to the Forum or go to Madison Square Garden and know what it’s like to have 35,000 people all looking at you, and you move your hand and feel everybody’s eyes watch what you’re doing. Or have them sing along with words that you made up in your basement about half a year ago when you were really depressed. Then all of a sudden there’s all these people singing it together, and you’re like, “Whoa, it’s cool.” You understand what evangelist preachers feel and to know what it’s like to have the power be so concentrated, and have the ability to use that power to go over and touch somebody and they jump back like they’ve been hit by lightning. That’s what being on stage with Devo in the early years was like.

I think that music has the power to change your life, and I do think it’s just like electronic force fields. It’s a great responsibility and a great buzz. Was it hard for you to go back to the film music and kind of be in the background rather than the foreground?

I know what you’re saying. But you know what? I saw those people that had been onstage, where I was five years before, waiting backstage, you saw the way they looked at you, and I go, “You know what? It’s not going to be forever and I’m going to enjoy it while it’s here.” And to be honest with you, Devo was a collaborative band. Although you’ll see people get credit for songs on albums, everybody contributed, because it was two sets of brothers originally. And to me, the idea of collaborating with a director and a producer, it feels more like Devo than if I would be just by myself doing solo records.

So you work well with others?

Yeah, I enjoy it.

Do you have a rule or a motto, something you say to yourself when you just don’t feel like getting up to do it in the morning?

God, I have no great quotes. I mean I try to live my life like a virgin.

What do you think your greatest strength is?

I enjoy solving problems. I’m a good problem solver everywhere in life. The big difference between Devo and KISS is, if the plumbing wasn’t working in the hotel room when we checked in, it probably worked when we left. And if the TV had snow on it we could, it was probably adjusted properly by the time we left the room. I can fix things, yeah. You know what? Save your brain for other stuff.

When you first came out with that line, “Are we not men? We are Devo,” was that a seminal moment in your life?

Yeah. It was a great moment. I was sitting in this shitty apartment in Akron, Ohio, $65 a month apartment, and I had quack religious pamphlets that I’d been collecting. I always invited Jehovah’s Witnesses in because they had great gravitas, and they were always attacking evolution. So they were the ones who got me thinking about all this great stuff – you know, things that I could use for pro-de-evolution. I could just use all their information so I would invite those people in and they’d stay around, and they’d walk around and look at all the masks I had on the walls, and I could hear them saying, “He has one room. He doesn’t have a bed. What is this? Is this a real apartment, or what is this? Hell?”

Would you overhear people saying, “Are we not men?” when you’d be out in the shopping mall or at the bank?

Yeah, but they always got it wrong. They said, “We are not men.” Dammit. Of course, a rhetorical question.

What’s something money can’t buy?

What can’t money buy? Peace of mind. No, it does buy it. What does it gain a man to have all the pussy in the world but to lose his soul? No, that’s not my motto.

What’s one thing that would surprise fans about you?

I think what surprises Rugrats fans is when they find out I was in Devo.

Let’s fast forward to today. In regards to the current tour, what prompted you to play the first two albums back to back as opposed to anything else?

The two-album-back-to-back concerts were inspired by Devo playing a string of parties back in London in May ’09. We were surprised that the first album, side 1 cut 1 through to side 2 last cut format worked so well, and wanted to let the Americanos get a chance to hear it.

Will the rest of the set list have some surprises for loyal fans?

Yes… and, uh, OK… yes! That said, I think the interesting part of this concept for a concert is, no surprises? Except extraordinarily good merch, for once.

Are you having a good time doing this music again? A while back you said you wouldn’t do DEVO again.

First off, it’s not about having a good time. We just do what we must do. I think I said “I wouldn’t ‘doo’ Devo, referring to wearing those uncomfortable plastic hair ‘doos’ we wore on the New Traditionalists album cover. Of course, none of us in the band have a lot of control over “doing” Devo; it’s in our genetic encoding.

How did the first two Devo albums end up getting remastered on 180g. vinyl? Was it a Devo decision or a Warner Bros. decision?

The vinyl remastering was spearheaded by Tom Biery at WB, I think. He loves vinyl as much as we do. I miss vinyl and not just for the sonic reasons.

Will we see the rest of the catalog remastered?

If WB hits black gold in some Burbank oil field soon, they may want to press a whole bunch of Devo albums.

What info can you leak to us about the new album? What else is up your yellow sleeves?

The new album is what our first albums would have been like if we would have had nurses to administer the drugs, and rascals to ride around on. Stay tuned.