“Who Is Interested? Well, I Am”

“Who Is Interested? Well, I Am”

A Conversation With Pink Floyd Drummer Nick Mason

By Bob Gendron

Pink Floyd’s forthcoming reissue series may represent the final time that a major artist’s full catalog receives the deluxe treatment in the manner of enhanced CDs, multiple box sets, redesigned packaging, and auxiliary analog reissues. In an era where most significant artists already witnessed their output re-released in remastered form, and where record labels are increasingly reluctant to manufacture box sets or invest in fancy physical media, EMI is celebrating the British group’s legacy with an exhaustive project that has few peers.

Going well beyond that of EMI’s excellent Beatles remasters series, Pink Floyd’s rollout features reconfigured sound, artwork, inserts, and more—as well as various multi-disc sets that include scads of unreleased and/or rare audio and visual footage. While the reissues don’t street until late September, drummer Nick Mason—the band’s only contiguous member—recently talked with editor Bob Gendron about various details, memories, and procedures related to the massive campaign. In clarifying truths and recalling history, his insightful comments will likely surprise even the most diehard Floyd fans and committed audiophiles.

B: You’ve heard Pink Floyd’s studio records countless times. What jumps out at you when you listen to the new remasters?

N: The thing that strikes me is not so much the quality, although that is interesting and improved. But [the pleasure] really comes from listening to things that I’ve forgotten about. For all of our career, we never really ever revisited old demos or leftover material. The tendency has always been to put that to one side when the record is finished or when we’ve moved on and started doing other shows. Sometimes, you come across ideas that are still quite fresh or interesting, and while they were superceded by some new idea, they still have validity in their own right.

B: Is there anything specific you heard that you feel the band should have revisited?

N: The one that astonishes me that we didn’t pick up on is a version of “Wish You Were Here” that has [violinist] Stephane Grappelli playing on it. First of all, it was just a delight to hear because I always understood that it had been recorded over and we had no record of it. But also, when I did hear it, I was astonished. And I haven’t done so yet, but I must ask Roger and David if they can remember why on earth we didn’t use it. It’s still incredibly powerful.

B: Having had the chance to survey the catalog again, what is the single piece of music closest to your heart?

N: A version of “On the Run,” recorded long before we actually put it together on the record with the VCS3 tape loop, where it’s played as sort of a jazz piece. It has a rather uptempo drum thing. I listened to it and thought, ‘Good lord, is that me playing?’ I hardly recognize the band, the style, or anything else. That sort of surprise is terrific.

B: Take me through some memories conjured up by the bonus material.

N: It conjures memories of touring in the early to mid 1970s, and putting on those shows. If you looked at the concerts now, you’d just think they were quaint—that’s the word for it. They are so small compared to not what we later did, but to what everyone does now. Virtually every artist today would expect to do quite a lot of staging and music production wherever they are playing. It’s that thing of remembering—the very early cherry pickers, for instance. Hydraulic towers with mounted lights. They are tiny now, but at the time, it was a really groundbreaking idea that you actually carried all of this stage lighting with you and made it part of the show.

B: Would you deem The Wall production “quaint” as well?

N: Quaint is the right word. The Wall came later, but if you look at, for instance, the Ummagumma sleeve: There is a picture of our touring crew and all of our equipment laid out. Well, most people have that in their back room now. It all fits into a small van. But at the time, it seemed like a gigantic amount of stuff. The Wall is interesting because the version that Roger is doing now is a fantastic leap—not so much musically because he’s adhered very rigorously to the original parts played on the record—in terms of the movie parts that have been added to the show. It’s fantastic, and absolutely 30 years further down the line.

B: Speaking of visuals, do you recall being associated with the visual content that’s now included on the box sets?

N: The visuals divide into different periods. There are three major periods: The stuff we originally did for Dark Side of the Moon, which was done by various people. There was an animator named Ian Eames who did a particular series of clocks that have stood the test of time. And then there was a second wave of film done by Hungarian film director Peter Medak. And then, finally, the Gerald Scarfe film that was done for Wish You Were Here. The interesting thing with his stuff is that some of it moved on; it was the forerunner of what got used in The Wall. I’m so used to computer animation now. The actual technology is quite clunky, but the visuals are stunning.

B: To what extent was the band involved in the visual design of the album artwork?

N: There’s no easy answer to that. Not unlike the way the music was put together, it was very different from image to image. The most famous one, the prism, by Storm [Thorgerson], arrived at the studio as five different rough ideas. Within an instant, all of us agreed that the prism was absolutely the right thing, and to go with Storm’s idea. We just rubber-stamped it immediately. There are other visuals where we went backwards and forwards, and in a few cases, there were ideas that initially came from the band and then, Storm developed them. Generally those ideas were less successful—I think Storm would back me up on that. [Laughs]

B: What’s your take on the reissue redesigns?

N: Terrific, because I’m of an age where I really do see physical records disappearing and regret that [trend]—and regret all of the artwork that goes with them. This is maybe not the very last chance, but very late on for Storm to really have another look at things, decide which is best, and add some new bits and pieces. For me, that’s one of the great attractions of the reissue project. We can make sure that every piece of visual art we’ve done, plus a bit more, is made available and there for the record, so to speak.

B: How long has the reissue project been in progress?

N: It’s been in the works for a couple of years. Of course, what happened is that the idea was mentioned two years ago and a lot of the push came from the record company, EMI, which said, ‘You know, you really ought to do this.’ We were initially very lukewarm. We felt that we’d done virtually every version of the catalog that we possibly could. But as the first year went by, we started unearthing more product that could go into it. And then we found ourselves becoming interested in it. It began to make more and more sense. For me, it was the realization that I actually [explore] with other artists. Like with jazz albums; I’ll go out and buy an eight-album John Coltrane box set, which is full of outtakes. And you think, well, ‘Who is interested?’ Well, I am. So if I’m interested in it with an artist, it makes sense to let our fans have access to such material.

B: Is the rare footage coming from personal or record label archives?

N: Most of it has come from EMI’s archives rather than our own. The only things that I’ve turned out have been some very early demos that we made before we were even signed, which contains some very nice Syd Barrett songs. But for the most part, it’s been EMI. The company has very extensive vaults and pretty good cataloging. But what happened this time is that there was a much more concerted effort to look through the archives. The trouble is that, like most archives, there are always a few things that have been miscataloged or haven’t been properly checked. This time, quite a lot of stuff was brought up from the vaults, listened to, and checked. That is how, for instance, the Grappelli version of “Wish You Were Here” got discovered.

B: The multichannel options seemingly parallel the unreleased material in that they represent new horizons for the listener. Do you think surround makes for a better experience?

N: I’m fond of the 5.1 and so on. I think it gives an extra depth to the music. But we’re all coming to terms with the fact that the embracing of the digital revolution wasn’t entirely satisfactory. It’s really interesting how many people are talking about going back to vinyl. You know, when I say ‘a lot of people,’ I mean a tiny percentage. I don’t think it’s really going to catch on. But there is still enormous enthusiasm for that warm, particularly odd sound you get from vinyl. And it’s not the cleanest, most accurate sound. But it does have this quality that people really like. To some extent, it will be really interesting to see the feedback. I’m not sure in this day and age how many people still have stereo sets capable of giving them the full effect. I was just talking with some people at breakfast this morning about the technical side of the reissues, and I said, ‘Maybe we should put a sort of health warning and say it is not advised to buy this record unless you have speakers that require at least two men to carry them into the room.’ [Laughs]

B: Regarding sonics, were you conscious when you were recording albums—especially Dark Side of the Moon, Wish You Were Here, and The Wall—that they would be, more than 30 years on, be used as references by producers, engineers, and audiophiles?

N: No. It’s astonishing in some ways. I think anyone who went into rock and roll in the 60s or early 70s entered into it with the belief that it was rock and roll and it was ephemeral and that it would be all over. Anything that you produced would last around a year, and in your working life, you’d be lucky to get five years. Of course, it changed. It became a completely different thing. The point I would like to get across is that if the quality of some of this stuff is so good—and I believe it is—it’s a testament to Abbey Road and the people that worked there and the systems they had in place in the 60s, where the kids joined as apprentices and really learned the trade of making records and miking things up and going for the highest standards of loading the tape.

B: It’s shocking to hear you admit that, even in the wake of The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, Pink Floyd believed it would disappear without a trace within a few years.

N: [Laughs] We’re all very privileged and lucky to have had a 40-odd-year career out of it. Obviously, after the first 10 or 15 years, you realize it’s not likely going to go away. But initially, in the late 60s, when we kicked off and had no idea where this would lead or end up, it’s what we thought.

“Who Is Interested? Well, I Am”

“Who Is Interested? Well, I Am” In an audiophile world where individual components have five (and sometimes six) figure price tags, the concept of being able to get a preamplifier and a pair of 200-watt mono amplifiers that use discrete circuitry instead of just being Class-D for under $1,200 is refreshing. You may have guessed that such components are manufactured offshore and sold direct to you from the manufacturer; both methods are necessary to keep costs down to this level. However, due to the high praise that greets Emotiva products, it appears that the company makes quality control a main priority.

In an audiophile world where individual components have five (and sometimes six) figure price tags, the concept of being able to get a preamplifier and a pair of 200-watt mono amplifiers that use discrete circuitry instead of just being Class-D for under $1,200 is refreshing. You may have guessed that such components are manufactured offshore and sold direct to you from the manufacturer; both methods are necessary to keep costs down to this level. However, due to the high praise that greets Emotiva products, it appears that the company makes quality control a main priority. Easy Listening

Easy Listening Taking a Spin

Taking a Spin Emotiva USP-1 Preamplifier and UPA-1 Amplifiers

Emotiva USP-1 Preamplifier and UPA-1 Amplifiers Yeah, yeah, we are pretty much the last ones to the party to discover the Spin Clean Record cleaner. But in case you haven’t heard of this incredibly reasonably priced record cleaning system that’s been around since 1975 and still made in the USA, it’s definitely worth your time. Dirt is the enemy of your records, it’s pretty much the enemy of the whole vinyl playback chain – it’s what makes for most of those nasty clicks and pops that the mainstream likes to tell us is “the romance of vinyl.”

Yeah, yeah, we are pretty much the last ones to the party to discover the Spin Clean Record cleaner. But in case you haven’t heard of this incredibly reasonably priced record cleaning system that’s been around since 1975 and still made in the USA, it’s definitely worth your time. Dirt is the enemy of your records, it’s pretty much the enemy of the whole vinyl playback chain – it’s what makes for most of those nasty clicks and pops that the mainstream likes to tell us is “the romance of vinyl.” But the room that gave me goosebumps was the Meridian room on the main floor featuring their 810 Video Projector. If you haven’t seen the 810 in action, it’s staggering. Imagine having an IMAX theater in your home. Yeah, it’s that good. For upwards of $200k for the system, you probably could spend the summer in style at Cannes next year, but you’d still have to go home to your boring 50-inch television. Once you’ve experienced the 810, your life will never be the same, it is by far the best video presentation I’ve ever had the pleasure of experiencing.

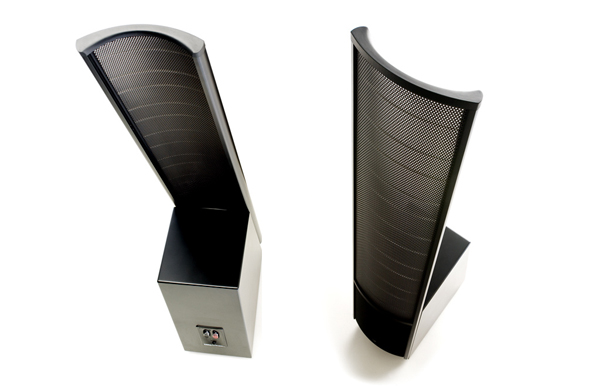

But the room that gave me goosebumps was the Meridian room on the main floor featuring their 810 Video Projector. If you haven’t seen the 810 in action, it’s staggering. Imagine having an IMAX theater in your home. Yeah, it’s that good. For upwards of $200k for the system, you probably could spend the summer in style at Cannes next year, but you’d still have to go home to your boring 50-inch television. Once you’ve experienced the 810, your life will never be the same, it is by far the best video presentation I’ve ever had the pleasure of experiencing. If you happen to be a music lover who adores electrostatic speakers, you no doubt have your favorites. And if MartinLogan is on your radar, its Aerius is definitely at the top of your list. Considering what an amazing value the Aerius offered back in 1992 for about $2000, the fact that MartinLogan has hit nearly the same price with its ElectroMotion is nothing less than a major miracle in 2011.

If you happen to be a music lover who adores electrostatic speakers, you no doubt have your favorites. And if MartinLogan is on your radar, its Aerius is definitely at the top of your list. Considering what an amazing value the Aerius offered back in 1992 for about $2000, the fact that MartinLogan has hit nearly the same price with its ElectroMotion is nothing less than a major miracle in 2011. Comparing Old and New

Comparing Old and New