Publisher’s Note: While I had a blast using the AudioQuest NightHawk headphones playing video games with my PS4, the team at AudioQuest did a lot of work on these wonderful headphones, so it only seemed proper that we put them through their paces as a “real headphone user” would.

Publisher’s Note: While I had a blast using the AudioQuest NightHawk headphones playing video games with my PS4, the team at AudioQuest did a lot of work on these wonderful headphones, so it only seemed proper that we put them through their paces as a “real headphone user” would.

So here is John Darko’s take on the NightHawk from that angle.

You can read more of John’s work here: http://www.digitalaudioreview.net We suggest you do so, he’s a clever chap.

But now, the review!

When AudioQuest asked exWestone engineer Skylar Gray to tackle their first headphone the design brief comprised only a single sentence: “Just make the best headphone you can make” . Implicit in this instruction was the new model would not be designed to a price. Early credit goes to Gray then for not going large and turning in a design that isn’t outrageously expensive by even today’s standards: a pair of NightHawk are yours for US$599.

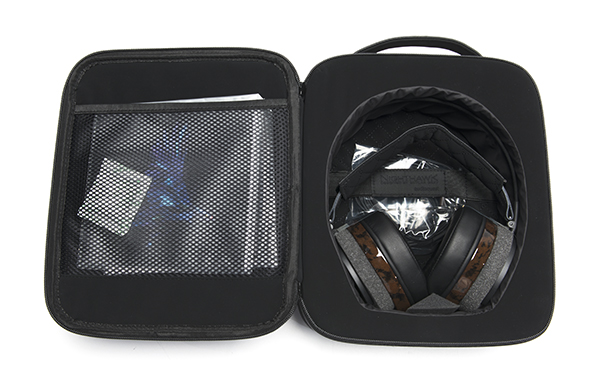

Following the notion that ‘everything matters’, no stone was left unturned throughout the design process. Firstly, from a consumer point of view, there’s the ‘unboxing’ that isn’t. Gray pushed hard to have AudioQuest dispense with wasteful outer packaging. The NightHawk’s leather carry case is wrapped in a simple cardboard sleeve. Detach and unzip.

When first pulling the NightHawk from their case it’s obvious that these headphones are a break from the norm. Their semi-open backed design concedes diddly squat to contemporary aesthetic trends. Working from the ground up, Gray attended to how each and every facet of a headphone can influence its sound. The headband is made from stainless steel and wrapped in two layers of resonance damping rubber before a final layer of fabric is applied. The headpad, made of leather and microsuede, suspends a semicircular yoke that in turn attaches to the earcup’s 3Dprinted grille via silicone bands, a material that was stress tested to five years’ wear and tear before being chosen over the less costly Neoprene (a distant second).

When first pulling the NightHawk from their case it’s obvious that these headphones are a break from the norm. Their semi-open backed design concedes diddly squat to contemporary aesthetic trends. Working from the ground up, Gray attended to how each and every facet of a headphone can influence its sound. The headband is made from stainless steel and wrapped in two layers of resonance damping rubber before a final layer of fabric is applied. The headpad, made of leather and microsuede, suspends a semicircular yoke that in turn attaches to the earcup’s 3Dprinted grille via silicone bands, a material that was stress tested to five years’ wear and tear before being chosen over the less costly Neoprene (a distant second).

Not only does this structural arrangement provide proper decoupling of ear cup from headband structure which can introduce unwanted resonances but it also has ergonomic advantages. If headphone comfort is of high priority, the NightHawk phones are up there with the best: they’re lightweight with only the mildest of lateral clamping force. The headband ensures that leaning forward doesn’t cause them to tumble off the head. If they do take a dive, these headphones’ seemingly fragile physicality could be their undoing; sans carrycase the NightHawks aren’t suited to bag life as well as other models (hello OPPO PM3).

Gray claims “a material with good acoustic properties” was required for the ear cups themselves. Kinda obvious, huh? Not so fast. The first casualty was a plastic that was not sustainable, leading Gray to test metal and wood. Viscoelastic rubber that turns sonic energy into heat wouldn’t sufficiently damp metal’s tendency to ring and wood didn’t pass muster due to its inherent inconsistencies, nor would it lend itself to being machined into complex shapes. MDF failed to pass muster because the corners were too easily damaged.

Liquid wood sidesteps the subtractive manufacturing process required by the other materials and is sustainable. Win and win. Those who have seen the dashboard of a recent luxury car will be familiar with the highgloss burl is capable of. It’s also used to make lampstands and shoe heels. What you might not know about liquid wood is that it arrives at the factory as a pellet. Only when heated does it change to the liquid state required for injection moulding. The liquid wood pellets for the NightHawk are sourced from Germany and moulded in China, where final headphone assembly also takes place. The grilles are 3Dprinted in France, with the driver magnets and aluminum parts sourced from Japan, making the NightHawk a true multicultural product.

However, AudioQuest remains tightlipped about the source of the NightHawk’s driver material for which Gray refused to go with off the shelf materials. “It’s not in my or AudioQuest’s DNA,” he says. “The norm.” as Gray describes it “is a Mylar film that works well in small sizes but is constantly flexing and changing shape.” The latter reportedly causes low frequency distortion adding colouration above 3kHz. Gray calls this the “easy, cheap route”.

After dismantling numerous similarly priced rival models Gray, like all good designers, asked, “How can I do this better?”. Sony’s long gone but much vaunted MDRR10 headphones take the inspirational credit for the NightHawk’s biocellulose driver, a material made from bacteria feces reportedly costing twelve times that of your average dynamic driver to make. This material comes to life by feeding bacteria cultures carbohydrates, causing them to excrete a fiber, cultivated after several weeks, then dried and cleaned before being pressed into 50 micron thick sheets. The 42mm NightHawk driver diagphragms are cookie cut from the sheets. An 8mm driver surround keeps the drivers pistonic motion from distorting the shape.

With their roots in cables, AudioQuest supplies two with the NightHawk: a thinner cable with gold plated plugs, not designed by AudioQuest themselves but able to withstand the bending and winding of mobile use. A second, thicker, solid core, balanced cable with silverplated connectors that won’t withstand endless bending, but takes design elements from the company’s loudspeaker cables, featuring “Solid Perfect Surface Copper+ (PSC+) conductors in a Double Star Quad configuration” is intended for serious, furrowed brow home listening (as conducted here by yours truly).

With their roots in cables, AudioQuest supplies two with the NightHawk: a thinner cable with gold plated plugs, not designed by AudioQuest themselves but able to withstand the bending and winding of mobile use. A second, thicker, solid core, balanced cable with silverplated connectors that won’t withstand endless bending, but takes design elements from the company’s loudspeaker cables, featuring “Solid Perfect Surface Copper+ (PSC+) conductors in a Double Star Quad configuration” is intended for serious, furrowed brow home listening (as conducted here by yours truly).

I’m not going to tell you that from the first note I was immediately struck by a sense of blah blah blah . In fact, nothing from the NightHawk’s presentation really stands out: no rambunctiousness (KEF M500), no overt bass heaviness (Sennheiser HD650), no super incisive treble (Sennheiser HD800). In trying to assess the NightHawk’s personality, I learnt that there wasn’t one to be found. That’s good for the would be buyer but gives a reviewer very little to get his teeth into.

I advise a little persistence to those dismissing the NightHawk as boring or plain after all but a casual audition. Their quirk free presentation will take time to win you over. More excitement can be had from the Sennheiser HD650 phones, which in turn aren’t as refined. However, you can’t run the HD650 so easily from a smartphone…which brings me to the NightHawk’s real talent: they don’t need a lot of juicing to get going. An iPhone or an Astell&Kern AK Jr. will suffice.

The NightHawk’s lean towards finesse and delicacy (as opposed to overall heft and weight) means they don’t necessarily benefit from the additional tonal colour of tubes. Straight talking amps are the order of the day here: the Resonessence Labs Herus or further up the food chain the Chord Hugo. Heck, even AudioQuest’s own Dragonfly is a solid match and one that will have upgraders struggling to justify the additional expense of only minor superior performance wrought by better amplification. That the NightHawk offers an exit ramp from the hamster wheel of upgrades brings ‘em into everyman headfi territory.

Moreover, these are headphones for an oft neglected section of the market: owners of integrated amplifiers whose headphone sockets don’t do justice to the likes of tougher loads from MrSpeakers, Mad Dog, or Beyerdynamic’s T1. The AudioQuest’s 100db efficiency displays none of those rivals’ tendency toward stridency when underpowered. After all, the headphone output on your average integrated amplifier is designed more to complete a functionality checklist than drive specialist headphones; only low-impedance models need apply. Thankfully, the NightHawk come it at 25 Ohms nominal, making them a shoe-in with portables and dongle DACs.

The upshot? You can’t please all of the people all of the time, but with their NightHawk headphone, AudioQuest gets pretty darn close.

MSRP: $599

www.audioquest.com

What started as a one-off unit intended as a family birthday gift has blossomed into a full-fledged audio equipment manufacturer. Hong Kong’s Clones Audio now counts monoblocks and a DAC among its product roster, but its 25i amplifier ($865/€629) is what jump-started the boutique manufacturer. The 25i, which is a 25 watts-per-channel integrated amplifier, was inspired by a 47 Labs’ circuit design that later landed in the public domain for the DIY crowd. After all, not everyone would see the $3,000-plus asking price of the 47 Labs’ Gaincard amp without wincing—and some might double over in pain upon seeing its internal part count.

What started as a one-off unit intended as a family birthday gift has blossomed into a full-fledged audio equipment manufacturer. Hong Kong’s Clones Audio now counts monoblocks and a DAC among its product roster, but its 25i amplifier ($865/€629) is what jump-started the boutique manufacturer. The 25i, which is a 25 watts-per-channel integrated amplifier, was inspired by a 47 Labs’ circuit design that later landed in the public domain for the DIY crowd. After all, not everyone would see the $3,000-plus asking price of the 47 Labs’ Gaincard amp without wincing—and some might double over in pain upon seeing its internal part count.

Schiit’s presentation also shows more connective tissue than the NFB-2.1; there are fewer spatial cues. If this DAC stand-off took place in the amplifier space, the Schiit would likely represent a tubular faction. Greater congeal means more forgiveness of poorer recordings and greater overall body. The thick synth lines underpinning Phones’ remix of The Rakes’ “Retreat” impact with more squelch than via the Chinese entry. The two units are pretty much matched for detail retrieval, with the Audio-gd stealing the lead with ambient decay.

Schiit’s presentation also shows more connective tissue than the NFB-2.1; there are fewer spatial cues. If this DAC stand-off took place in the amplifier space, the Schiit would likely represent a tubular faction. Greater congeal means more forgiveness of poorer recordings and greater overall body. The thick synth lines underpinning Phones’ remix of The Rakes’ “Retreat” impact with more squelch than via the Chinese entry. The two units are pretty much matched for detail retrieval, with the Audio-gd stealing the lead with ambient decay. The Schiit Bifrost DAC

The Schiit Bifrost DAC